Adam2.org Award-winning Articles . . .

Title: A History Of Culture Wars

Author: Michael Barone

Source: U.S. News & World Report

Date: August 1, 1994

Re: "On Politics" page 40.

Permission for reprint requested: 02/07/2001

Contributor: Anonymous

A History Of Culture Wars

- by Michael Barone

"Out of one, many," Vice President Al Gore declared last year, mistranslating the national motto, e pluribus unum . He went on to suggest America had moved from a single culture to diversity for "all our separate identities." This mistake perhaps comes naturally to a baby boomer who remembers the white bread, Ozzie-and-Harriet image of America in the 1950s and contrasts it with the "multicultural" America of the 1990s, with its highly visible blacks, Hispanics, and Asians.

But America, even in the post-World War II years of apparent conformity, always has been a culturally diverse country where deeply held differences on values have occasionally erupted into political and even military conflict. Colonial America was peopled with Calvinists, Anglicans, Catholics, Mennonites and Jews. These settlers, writes historian David Hackett Fischer, were heavily influenced by cultural attitudes from different parts of Britain that produced conflicting outlooks toward everything from religion and money to sport and sex. This diversity persisted in a nation whose geographic expanse and mostly nonintrusive government let most people go their own way. "What has held Americans together," writes historian Robert Wiebe in The Segmented Society, "is their capacity for living apart."

Values in conflict. In an America where, as Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in the 1830s, religion is "the first of political institutions," values have often led to political conflict when fervent believers clashed over public policy. The religious and cultural values that made some Americans cherish and other abhor the French Revolution produced the bitter party divisions of the late 1790s, when the new nation caught up in a world war between France and Britain nearly split apart.

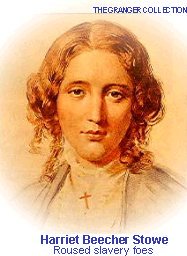

In the 1850s, the values of reformers from New England and crusaders such as Harriet Beecher Stowe clashed with the Cavalier culture of the South over the issue of slavery.

Yankee values were embodied in the new Republican Party, whose Southern-born candidate won the presidency with a plurality and redefined the nation as he won the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln could not have done that without strengthening government's powers—raising vast armies, suspending habeas corpus, levying income taxes and printing greenbacks—beyond what America had ever seen.

In the 1850s, the values of reformers from New England and crusaders such as Harriet Beecher Stowe clashed with the Cavalier culture of the South over the issue of slavery.

Yankee values were embodied in the new Republican Party, whose Southern-born candidate won the presidency with a plurality and redefined the nation as he won the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln could not have done that without strengthening government's powers—raising vast armies, suspending habeas corpus, levying income taxes and printing greenbacks—beyond what America had ever seen.

After the Civil War receded, the economy grew, government influence faded and most Americans were again free to indulge their own values privately. But the Progressive Era and, even more, World War I showed that a powerful state could not regulate conduct, and WASPish elites decided to use government to advance cultural values. Some efforts succeeded, while others failed. The women's movement got the vote but not equality. Prohibition cut alcohol consumption in most of the country but was unenforceable in big cities and was gladly abandoned in 1933. Immigration restriction, an attempt to bar supposedly alien cultures, lasted longer; the tough laws of 1921 and 1924 were eased only in 1965, 1986 and 1990. So the America of the 1950s, with the lowest proportion of foreign born residents in a century, really did lack diversity in one important way.

The government grew more powerful still in World War II. It put most young men in uniform, then helped steer them to college campuses, suburban homes and large families. One wise observer said Americans at that time shared a "civil religion," a set of values geared to work, family, education and order that went largely unchallenged. Soon they were. Urban rioting and student rebellions created a sense of disorder and sparked the backlash that elected Ronald Reagan California's governor in 1966 and Richard Nixon president in 1968. Believers in antiwar, feminist and secular values, feeling their space invaded, organized politically and achieved many of their goals, some in government but even more in influencing the culture. Meanwhile, believers in traditional values, feeling their space invaded by hostile beaucrats and coarsening media, organized politically and achieved some of their goals, especially in the 1980s presidential elections. Today, they supply the dominant energy in the Republican Party. On one issue after another—abortion, gay rights, race and gender quotas—the conflict between the values of the feminist left and the values of the religious right frames the political discussion.

Most practical politicians would like to see values-laden issues go away. But what is more important? Americans, scholar Michael Novak argues, have shown we know how to build a prosperous economy and a successful foreign policy; the problems are at the margins. But over the past generation we have not built a successful culture, one that raises a generation better than the one before. So values politics will likely continue.

Recommended Additional Reading - N.Y.Times Best Seller

Description:

"Bold, powerful, and persuasive, The Death of the West details how a civilization, culture, and moral order are passing away and foresees a new world order that has terrifying implications for our freedom, our faith, and the preeminence of American democracy".