HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

SECTIONS: I. America as

Refuge - II. 18th Century

America

III. American Revolution - IV. Congress of the

Confederation - V. State

Governments

VI. Federal

Government - VII. New

Republic

III. Religion and the American Revolution

Religion played a

major role in the American Revolution by offering a moral sanction for

opposition to the British--an assurance to the average American that

revolution was justified in the sight of God. As a recent scholar has

observed, "by turning colonial resistance into a righteous cause, and by

crying the message to all ranks in all parts of the colonies, ministers

did the work of secular radicalism and did it better."

Ministers served the American cause in many capacities during the

Revolution: as military chaplains, as penmen for committees of

correspondence, and as members of state legislatures, constitutional

conventions and the national Congress. Some even took up arms, leading

Continental troops in battle.

The Revolution split some denominations, notably the Church of England,

whose ministers were bound by oath to support the King, and the Quakers,

who were traditionally pacifists. Religious practice suffered in certain

places because of the absence of ministers and the destruction of

churches, but in other areas, religion flourished.

The Revolution strengthened millennialist strains in American theology.

At the beginning of the war some ministers were persuaded that, with God's

help, America might become "the principal Seat of the glorious Kingdom

which Christ shall erect upon Earth in the latter Days." Victory over the

British was taken as a sign of God's partiality for America and stimulated

an outpouring of millennialist expectations--the conviction that Christ

would rule on earth for 1,000 years. This attitude combined with a

groundswell of secular optimism about the future of America to create the

buoyant mood of the new nation that became so evident after Jefferson

assumed the presidency in 1801.

Religion as Cause of the

Revolution Religion as Cause of the

Revolution

Joseph Galloway (1731-1803), a former speaker

of the Pennsylvania Assembly and close friend of Benjamin Franklin,

opposed the Revolution and fled to England in 1778. Like many Tories

he believed, as he asserted in this pamphlet, that the Revolution

was, to a considerable extent, a religious quarrel, caused by

Presbyterians and Congregationalists whose "principles of religion

and polity [were] equally averse to those of the established Church

and Government."

Historical

and Political Reflections on the Rise and Progress

of the

American Rebellion [page 54] - [page

55]

Joseph Galloway, London: G. Wilkie, 1780

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division, Library of Congress (81)

Jonathan

Mayhew Jonathan

Mayhew

An eloquent proponent of the idea that civil and

religious liberty was ordained by God, Jonathan Mayhew considered

the Church of England as a dangerous, almost diabolical, enemyof the

New England Way. The bishop's mitre with the snake emerging from it

represented his view of the Anglican hierarchy.

Jonathan

Mayhew, D.D. Pastor of the West Church in Boston . .

.

Etching by Giovanni Cipriani, London: 1767

The

American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts (82)

Resistance to Tyranny as

a Christian Duty Resistance to Tyranny as

a Christian Duty

Jonathan Mayhew delivered this

sermon--one of the most influential in American history--on the

anniversary of the execution of Charles I. In it, he explored the

idea that Christians were obliged to suffer under an oppressive

ruler, as some Anglicans argued. Mayhew asserted that resistance to

a tyrant was a "glorious" Christian duty. In offering moral sanction

for political and military resistance, Mayhew anticipated the

position that most ministers took during the conflict with

Britain.

Discourse

Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher

Powers

Jonathan Mayhew, D.D.

Boston: D. Fowle and

D. Gookin,1750

Rare

Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

(83)

Revolution Understood in

Scriptural Terms Revolution Understood in

Scriptural Terms

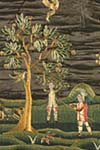

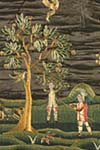

Thought to have been created soon after

the Boston Massacre of 1770, this needlework is an excellent example

of how many colonists understood political events in terms of

familiar Bible stories. The creator of the work saw Absalom as a

patriot, rebelling against and suffering from the arbitrary rule of

his father King David (symbolizing George III). The king, shown at

the top left, is playing his harp, evidently oblivious to the

anguish of his children in the American colonies. The figure

executing Absalom--David's commander Joab in the Old Testament

story--is dressed as a British red coat.

The

Hanging of Absalom

Silk, Weft-silk fabric, foil

wrapped threads, paper, watercolor,

attributed to Faith Robinson

Trumbull (1718-1780) c. 1770

Lyman Allyn Art Museum at

Connecticut College, New London, Connecticut (84)

The Plot to Land a

Bishop The Plot to Land a

Bishop

The supposed British plot, to impose Anglican

bishops in the colonies, aroused atavistic fears that Americans

would be persecuted for their religious convictions and further

poisoned relations between Britain and the colonies. In this cartoon

an indignant New England mob pushes a bishop's boat back towards

England, frightening the prelate into praying, "Lord, now lettest

thou thy Servant depart in Peace." The mob flings a volume of

Calvin's Works at the bishop, while brandishing copies of John Locke

and Algernon Sydney on government. The crowd shouts slogans:

"Liberty & Freedom of Conscience"; "No Lords Spiritual or

Temporal in New England"; and "shall they be obliged to maintain

bishops that cannot maintain themselves."

An Attempt

to Land a Bishop in America

Engraving from the

Political Register

London: September, 1769

John Carter

Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, RI (86)

Revolution Justified by

God Revolution Justified by

God

Many Revolutionary War clergy argued that the war

against Britain was approved by God. In this sermon Abraham Keteltas

celebrated the American effort as "the cause of truth, against error

and falsehood . . .the cause of pure and undefiled religion, against

bigotry, superstition, and human invention . . .in short, it is the

cause of heaven against hell--of the kind Parent of the Universe

against the prince of darkness, and the destroyer of the human

race."

God

Arising And Pleading His People's Cause; Or The American War . . .

Shewn To Be The Cause Of God

Abraham

Keteltas

Newbury-Port: John Mycall for Edmund Sawyer, 1777

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division, Library of Congress (87)

A Minister in

Arms A Minister in

Arms

This satire expresses the British view that the

American Revolution was inspired by the same kind of religious

fanaticism that had fueled Oliver Cromwell's establishment of the

Commonwealth of England more than a century earlier. Among the

ragtag American soldiers is a clergyman holding a flag with a

Liberty Tree on it and claiming " Tis Old Olivers Cause no Monarchy

nor Laws."

The Yankie

Doodles Intrenchments Near Boston 1776

Etching.

Copyprint

British Museum, London, England (88)

A Fighting

Parson A Fighting

Parson

Peter Muhlenberg (1746-1807) was the prime

example of a "fighting parson" during the Revolutionary War. The

eldest son of the Lutheran patriarch Henry Melchoir Muhlenberg,

young Muhlenberg at the conclusion of a sermon in January 1776 to

his congregation in Woodstock, Virginia, threw off his clerical

robes to reveal the uniform of a Virginia militia officer. Having

served with distinction throughout the war, Muhlenberg commanded a

brigade that successfully stormed the British lines at Yorktown. He

retired from the army in 1783 as a brevetted major general.

John Peter

Gabriel Muhlenberg

Oil on canvas, by an unidentified

American artist

Nineteenth century

Martin Art Gallery,

Muhlenberg College, Allentown, Pennsylvania (89)

A Revolutionary

Chaplain A Revolutionary

Chaplain

James Caldwell (1734-1781), a Presbyterian

minister at Elizabeth, New Jersey, was one of the many clergymen who

served as chaplains during the Revolutionary War. At the battle of

Springfield, New Jersey, on June 23, 1780, when his company ran out

of wadding, Caldwell was said to have dashed into a nearby

Presbyterian Church, scooped up as many Watts hymnals as he could

carry, and distributed them to the troops, shouting "put Watts into

them, boys." Caldwell and his wife were both killed before the war

ended.

Reverend

James Caldwell at the Battle of Springfield

Watercolor by Henry Alexander Ogden

Presbyterian

Historical Society, Philadelphia (90)

Revolutionary Battle

Flag Revolutionary Battle

Flag

Like this one, many battle flags of the American

Revolution carried religious inscriptions.

Gostelowe

Standard No. 10, c. 1776

Watercolor once in possession

of Edward W. Richardson. Copyprint

Courtesy of the Pennsylvania

Society of Sons of the Revolution

and Its Color Guard (91)

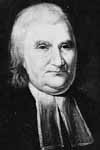

John

Witherspoon John

Witherspoon

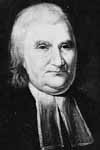

John Witherspoon (1723-1794) was the most

important "political parson" of the Revolutionary period. He

represented New Jersey in the Continental Congress from 1776 to

1782, in which capacity he signed the Declaration of Independence

and served on more than one hundred committees. As president of

Princeton, Witherspoon was accused of turning the institution into a

"seminary of sedition."

John

Witherspoon

Oil on canvas, by Rembrandt Peale after

Charles Wilson Peale, 1794

National Portrait Gallery, Washington,

D.C. (92)

A Quaker

Schism A Quaker

Schism

Some Quakers were conscientiously convinced that

they could, despite the Friends' peace testimony, take up arms

against the British. Calling themselves "Free Quakers," they

organized in Philadelphia. The majority of Quakers adhered to the

denomination's traditional position of pacifism and disowned their

belligerent brethren. This Free Quaker broadside declares that

although the "regular" Quakers have "separated yourselves from us,

and declared that you have no unity with us," the schism does not

compromise the Free Quakers' rights to common property.

To those

of our Brethren who have disowned us.

Broadside, July

9, 1781

Manuscript

Division, Library of Congress (93)

Free Quaker Meeting

House Free Quaker Meeting

House

The Free Quakers built their own Meeting House in

Philadelphia.

Free

Quaker Meeting House,

SW corner 5th and Arch St.,

Philadelphia, Pa.

Photograph

Manuscript Division, Library

of Congress (94)

|

THE PROBLEMS OF THE AMERICAN ANGLICANS

| The American Revolution inflicted deeper

wounds on the Church of England in America than on any other

denomination because the King of England was the head of the church.

Anglican priests, at their ordination, swore allegiance to the King.

The Book of Common Prayer offered prayers for the monarch,

beseeching God "to be his defender and keeper, giving him victory

over all his enemies," who in 1776 were American soldiers as well as

friends and neighbors of American Anglicans. Loyalty to the church

and to its head could be construed as treason to the American cause.

Patriotic American Anglicans, loathe to discard so fundamental a

component of their faith as The Book of Common Prayer,

revised it to conform to the political realities.

|

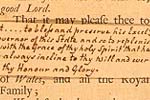

Maryland's Revised Book

of Common Prayer Maryland's Revised Book

of Common Prayer

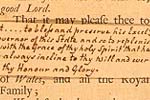

The Maryland Convention voted on May

25, 1776, "that every Prayer and Petition for the King's Majesty, in

the book of Common Prayer . . . be henceforth omitted in all

Churches and Chapels in this Province." The rector of Christ Church

(then called Chaptico Church) in St. Mary's County, Maryland, placed

over the offending passages strips of paper showing prayers composed

for the Continental Congress. The petition that God "keep and

strengthen in the true worshipping of thee, in righteousness and

holiness of life, thy servant GEORGE, our most gracious King and

Governour" was changed to a plea that "it might please thee to bless

the honorable Congress with Wisdom to discern and Integrity to

pursue the true Interest of the United States."

Book of

Common Prayer

England: John Baskerville, c.

1762

Washington National Cathedral Rare Books Library (95)

|

Christ Church,

Philadelphia's Revised Book of Common Prayer Christ Church,

Philadelphia's Revised Book of Common Prayer

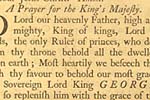

The problem

was handled differently by Christ Church, Philadelphia. The rector,

the Reverend Jacob Duch, called a special vestry meeting on July 4,

1776, to ask whether it was advisable "for the peace and welfare of

the congregation, to shut up the churches or to continue the

service, without using the prayers for the Royal Family." The vestry

decided to keep the church open but replace the prayers for the King

with a prayer for Congress: "That is may please thee to endue the

Congress of the United States & all others in Authority,

legislative, executive, & judicial with grace, wisdom &

understanding, to execute Justice and to maintain Truth."

Book of

Common Prayer

London: Mark Basket, 1766

Courtesy of

the Rector, Church Wardens, and Vestrymen of Christ Church,

Philadelphia (96)

Book of

Common Prayer [left page] - [right

page]

Here is a facsimile of the page from the Book of

Common Prayer,

containing the prayers for the king, that were

altered in various ways.

Oxford: Printed by Mark Basket, printer

to the University, 1763

Copyprint

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division, Library of Congress (95a)

A Tory Preacher on the

Attack A Tory Preacher on the

Attack

More than half of the Anglican priests in

America, unable to reconcile their oaths of allegiance to George III

with the independence of the United States, relinquished their

pulpits during the Revolutionary War. Some of the more intrepid

priests put their loyalty to the Crown at the service of British

forces in America. One of these, Jonathan Odell (1737-1818), rector

at Burlington, New Jersey, became a confidant of Benedict Arnold and

scourged the Patriots with a sharp, satirical pen. This long, rhymed

attack on John Witherspoon contains the clumsy couplet, "Whilst to

myself I've humm'd in dismal tune, I'd rather be a dog than

Witherspoon." Odell blasted his fellow Anglican ministers, who

supported the American cause, for apostasy.

The

American Times: A Satire in Three Parts in which are delineated . .

. the Leaders of the American Rebellion

Jonathan Odell,

London: 1780

Rare

Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

(97)

An Argument for an

American Episcopal Church An Argument for an

American Episcopal Church

In the years following

American independence, Anglican ministers who had remained in the

colonies began planning for an independent American church. One of

the publications that focused discussion on the issue was this

volume by William White. A series of conferences in the 1780s failed

to bridge the differences between two parties that emerged but, at a

convention in 1789, the two groups formed the Protestant Episcopal

Church of the United States. A church government and revised Book of

Common Prayer believed to be compatible with a rising democratic

nation were adopted.

The Case

of the Episcopal Churches in the United States Considered

William White

Philadelphia: David Claypoole,

1782

Rare Book and

Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (98)

The Establishment of the

Methodist Episcopal Church The Establishment of the

Methodist Episcopal Church

The independence of the

United States stimulated American Methodists, as it did their

brethren in the Church of England, with whom the Methodists had

considered themselves "in communion," to organize themselves as an

independent, American church. This happened at the Christmas

Conference in Baltimore in 1784, where Francis Asbury and Thomas

Coke were elected as superintendents of the new Methodist Episcopal

Church. Asbury was ordained as deacon, elder, and superintendent.

American Methodists adopted the title of bishop for their leaders

three years later.

The

Ordination of Bishop Asbury, and the Organization of the Methodist

Episcopal Church.

Engraving by A. Gilchrist Campbell,

1882, after a painting by Thomas Coke Ruckle

Prints and Photographs

Division, Library of Congress.

Gift of the Lovely Lane

Museum, Baltimore (99)

![Acts and Proceedings of the Synod of New-York and Philadelphia, A.D.1787, & 1788 [right]](images/vc6770th.jpg) ![Acts and Proceedings of the Synod of New-York and Philadelphia, A.D.1787, & 1788 [left]](images/vc6769th.jpg) Reforms in the

Presbyterian Church Reforms in the

Presbyterian Church

Like the Anglicans and Methodists,

Presbyterians reorganized their church as a distinctly American

entity, thereby reducing some of the influence of the Church of

Scotland. From debates at the synods of 1787 and 1788 emerged a new

Plan of Government and Discipline, a Directory of Public Worship,

and a revised version of the Westminster Confession, which was made

"a part of the constitution." In the proceedings of the 1787 and

1788 synods, shown here, the Presbyterian Church, along with other

contemporary American churches, took a stand against slavery,

recommending that Presbyterians work to "procure, eventually, the

final abolition of slavery in America."

Acts and

Proceedings of the Synod of New-York

and Philadelphia, A.D.1787,

& 1788 [left page] - [right

page]

Philadelphia: Francis Bailey, 1788

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division, Library of Congress (100)

|

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

SECTIONS: I. America as

Refuge - II. 18th Century

America

III. American Revolution - IV. Congress of the

Confederation - V. State

Governments

VI. Federal

Government - VII. New

Republic

Go to:

Library of Congress Library of Congress

Comments: Contact Us

(06/03/98)

|

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

![Acts and Proceedings of the Synod of New-York and Philadelphia, A.D.1787, & 1788 [right]](images/vc6770th.jpg)

![Acts and Proceedings of the Synod of New-York and Philadelphia, A.D.1787, & 1788 [left]](images/vc6769th.jpg)