HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

SECTIONS: I. America as

Refuge - II. 18th Century

America

III. American

Revolution - IV. Congress of the

Confederation - V. State Governments

VI. Federal

Government - VII. New

Republic

V. Religion and the State Governments

Many states were as

explicit about the need for a thriving religion as Congress was in its

thanksgiving and fast day proclamations. The Massachusetts Constitution of

1780 declared, for example, that "the happiness of a people, and the good

order and preservation of civil government, essentially depend on piety,

religion and morality." The states were in a stronger position to act upon

this conviction because they were considered to possess "general" powers

as opposed to the limited, specifically enumerated powers of Congress.

Congregationalists and Anglicans who, before 1776, had received public

financial support, called their state benefactors "nursing fathers"

(Isaiah 49:23). After independence they urged the state governments, as

"nursing fathers," to continue succoring them. Knowing that in the

egalitarian, post-independence era, the public would no longer permit

single denominations to monopolize state support, legislators devised

"general assessment schemes." Religious taxes were laid on all citizens,

each of whom was given the option of designating his share to the church

of his choice. Such laws took effect in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and

New Hampshire and were passed but not implemented in Maryland and Georgia.

After a general assessment scheme was defeated in Virginia, an

incongruous coalition of Baptists and theological liberals united to

sunder state from church. However, the outcome in Virginia of the

state-church debate did not, it should be remembered, represent the views

of the majority of American states that wrestled with this issue in the

1780s.

"NURSING FATHERS" OF THE CHURCH

Queen Elizabeth I as

Nursing Mother to the Church Queen Elizabeth I as

Nursing Mother to the Church

John Jewel, Bishop of

Salisbury (1522-1571), has been called the "father of the Church of

England," because his tract, The Apologie of the Church of

England (London, 1562), was "the first methodical statement of

the position of the Church of England against the Church of Rome."

Jewel's Apologie was attacked by Catholic spokesmen,

eliciting from him the Defense of his original publication,

seen here, in which he saluted Queen Elizabeth, using Isaiah's

metaphor, as the "Nource" of the church.

A Defense

of the Apologie of the Churche of Englande

John Jewel

, London: Henry Wykes, 1570

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division,

Library of Congress (121)

The Westminster

Confession of Faith The Westminster

Confession of Faith

The Westminster Confession of Faith,

the "creed" of the Presbyterian Church in Scotland and the American

colonies, was drafted by a convention of ministers summoned by the

Long Parliament in 1643. In the revised creed, adopted by the

Presbyterian Church in the United States in 1788, "nursing fathers"

was elevated from an explanatory footnote--(note f), as it appears

here, to the body of the text in the section on the duties of the

civil magistrate. The concept of the state as a nursing father

provided the theological justification for some American

Presbyterians to approve the idea of state financial support for

religion.

The

Humble Advice of the Assembly of Divines

by Authority of

Parliament sitting at Westminster;

Concerning a Confession of

Faith

London: S. Griffin, 1658

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division,

Library of Congress (122)

|

During the debates in the 1780s about the

propriety of providing financial support to the churches, those who

favored state patronage of religion urged their legislators, in the

words of petitioners from Amherst County, Virginia, in 1783, not "to

think it beneath your Dignity to become Nursing Fathers of the

Church." This idea was an old one, stretching back to the dawn of

the Reformation. The term itself was drawn from Isaiah 49:23, in

which the prophet commanded that "kings shall be thy nursing

fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers." The responsibilities

of the state were understood in an early work like Bishop John

Jewel's Apologie of the Church of England (1562) to be

comprehensive, including imposing the church's doctrine on society.

The term "nursing father" was used in all American colonies with

established churches. It appeared in the Cambridge Platform of 1648,

the "creed" of New England Congregationalism; in numerous Anglican

writings; and in the Presbyterian Westminster Confession. By the

time of the American Revolution, the state was no longer expected to

maintain religious uniformity in its jurisdiction, but it was

expected to use its resources for the churches' benefit.

|

Civil Rulers as Nursing

Fathers Civil Rulers as Nursing

Fathers

This is one of the many public statements in New

England of the "nursing fathers" concept. After independence the

phrase was sometimes modified to "political fathers."

The Duty of

Civil Rulers, to be nursing Fathers to the Church of Christ. A

Sermon. . . .

Edward Dorr, Hartford: Thomas Green,

1765

Rare Book and

Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

(123)

British Government as

Nursing Fathers British Government as

Nursing Fathers

In this proclamation, the British

government was reproved for not supporting the church in

Massachusetts: "those who should be Nursing Fathers become its

Persecutors."

Fast Day

Proclamation, April 15, 1775

Massachusetts Provincial

Congress, Broadside

Rare Book and Special Collections Division,

Library of Congress (124)

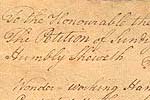

The Virginia Assembly as

Nursing Fathers The Virginia Assembly as

Nursing Fathers

This petition asks that members of the

Virginia Assembly play their traditional role as "Nursing Fathers"

of the church.

Petition

to the Virginia Assembly from Amherst County,

Virginia, November

27, 1783 [page one] - [page

two] - [page

three] - [page

four]

The Library of Virginia (125)

|

THE CHURCH-STATE DEBATE: MASSACHUSETTS

| After independence the American states were

obliged to write constitutions establishing how each would be

governed. In no place was the process more difficult than in

Massachusetts. For three years, from 1778 to 1780, the political

energies of the state were absorbed in drafting a charter of

government that the voters would accept. A constitution prepared in

1778 was decisively defeated in a public referendum. A new

convention convened in 1779 to make another attempt at writing an

acceptable draft.

One of the most contentious issues was whether the state would

support religion financially. Advocating such a policy--on the

grounds that religion was necessary for public happiness,

prosperity, and order--were the ministers and most members of the

Congregational Church, which had been established, and hence had

received public financial support, during the colonial period. The

Baptists, who had grown strong since the Great Awakening,

tenaciously adhered to their ancient conviction that churches should

receive no support from the state. They believed that the Divine

Truth, having been freely received, should be freely given by Gospel

ministers.

The Constitutional Convention chose to act as nursing fathers of

the church and included in the draft constitution submitted to the

voters the famous Article Three, which authorized a general

religious tax to be directed to the church of a taxpayers' choice.

Despite substantial doubt that Article Three had been approved by

the required two thirds of the voters, in 1780 Massachusetts

authorities declared it and the rest of the state constitution to

have been duly adopted. |

For Tax-Supported

Religion For Tax-Supported

Religion

Phillips Payson (1736-1801), Congregational

minister at Chelsea, was a pillar of the established church in

Massachusetts. Payson was widely admired for leading an armed group

of parishioners into battle at Lexington in 1775. In this Election

Sermon, Payson used an argument that was a staple of the

Massachusetts advocates of state support of religion, insisting that

"the importance of religion to civil society and government is great

indeed . . . the fear and reverence of God and the terrors of

eternity, are the most powerful restraints on the minds of men . . .

let the restraints of religion once be broken down . . . and one

might well defy all human wisdom and power to support and preserve

order and government in the state."

A sermon

preached before the honorable Council,

and the honorable House of

Representatives,

of the State of Massachusetts-Bay, in

New-England,

at Boston, May 27, 1778

Phillips

Payson, Boston: John Gill, 1778

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division,

Library of Congress (126)

Against Tax-Supported

Religion Against Tax-Supported

Religion

Isaac Backus (1724-1806) was the leader of the

New England Baptists. In this response to Payson's Election Sermon,

Backus forcefully states the Baptists' opposition to state support

of the churches. This opposition was grounded in the Baptists'

reading of the New Testament and also of ecclesiastical history

which demonstrated, that state support of religion inevitably

corrupted the churches. Backus and other Baptist leaders agreed with

their clerical adversaries in believing that religion was necessary

for social prosperity and happiness but they believed that the best

way for the state to assure the health of religion was to leave it

alone and let it take its own course, which, the Baptists were

convinced, would result in vital, evangelical religion covering the

land.

Government

and Liberty Described

and Ecclesiastical Tyranny Exposed

Isaac Backus, Boston: Powars and Willis,

1778

Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library,

Brown

University (127) |

Rev. Isaac

Baccus, AM.

Trask Library, Andover Theological

Seminary,

Newton Centre, Massachusetts (128)

Another Advocate of

Tax-Supported Religion Another Advocate of

Tax-Supported Religion

In Massachusetts, a newspaper war

raged for years over state support of religion. One of the most

indefatigable combatants on the side of state support was Samuel

West (1730-1807), Congregational minister at Dartmouth,

Massachusetts, who performed valuable code-breaking services for the

American Army during the Revolutionary War. Here West, writing as

"Irenaeus," uses the familiar argument that religion with its

"doctrine of a future state of reward and punishment" provides a

greater inducement to obedience to the law than civil punishments.

It is, as a result, so indispensable for the maintenance of social

order that its support must be assured by the state, not left to

private initiative.

The

Boston Gazette and the Country Journal, November 27, 1780.

"Irenaeus"

Serial and Government

Publications Division, Library of Congress (129)

![A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts [right page]](images/f0503bth.jpg) ![A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts [left page]](images/f0503ath.jpg) Massachusetts

Constitution of 1780 Massachusetts

Constitution of 1780

Article Three of the Bill of Rights

of the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 asserted that "the

happiness of a people, and the good order and preservation of civil

government, essentially depend on piety, religion and morality."

A

Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts

from Account of Frame of Government agreed

upon

by the Delegates of the People. . . .[left page] - [right

page]

Boston: Benjamin Edes & Sons, 1780.

Copyprints

Rare Book

and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (130-130a

)

An Appeal for

Tax-Supported Religion in Maryland An Appeal for

Tax-Supported Religion in Maryland

An example of the

influence of Article Three of the Massachusetts Constitution is this

broadside issued by the Maryland House of Delegates in 1785 as part

of a campaign to win public support for a general religious tax. The

first sentence of this broadside paraphrases Article Three.

Proposed

Resolution of the Maryland House of

Delegates.

Broadside, January 12, 1785

Broadside

Collection, Rare Book

and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (131)

|

THE CHURCH-STATE DEBATE: VIRGINIA

A Proposal for

Tax-Supported Religion for Virginia A Proposal for

Tax-Supported Religion for Virginia

This broadside

contains (at the bottom) the opening sections of Patrick Henry's

general assessment bill, one similar to those passed in the New

England states. The bill levied a tax for the support of religion

but permitted individuals to earmark their taxes for the church of

their choice. At the top of the broadside are the results of a vote

in the Virginia General Assembly to postpone consideration of the

bill until the fall 1785 session of the legislature. Postponing the

bill allowed opponents to mobilize and defeat it. Leading the forces

for postponement was James Madison. Voting against postponement and,

therefore, in support of a general tax for religion was the future

Chief Justice of the United States, John Marshall.

A Bill

Establishing a Provision for Teachers

of the Christian

Religion, Patrick Henry,

Virginia House of Delegates,

December 24, 1784. Broadside

Manuscript Division, Library

of Congress (133)

Patrick

Henry Patrick

Henry

Stipple engraving by Leney, after Thomas

Sully

Published by J. Webster, 1817, Copyprint

Prints and Photographs

Division

(LC-USZ62-4907)

Library of Congress (134)

James

Madison James

Madison

Miniature portrait by Charles Willson Peale,

1783

Rare Book and

Special Collections Division

(USZ62-5310)

Library of

Congress (135)

John

Marshall John

Marshall

Engraving with ink and ink wash, by

Charles-Balthazar-Julien Fevret de Saint-Mmin, 1808

Prints and Photographs

Division

(LC-USZ62-54940)

Library of Congress (136)

|

In 1779 the Virginia Assembly deprived

Church of England ministers of tax support. Patrick Henry sponsored

a bill for a general religious assessment in 1784. He appeared to be

on the verge of securing its passage when his opponents neutralized

his political influence by electing him governor. As a result,

legislative consideration of Henry's bill was postponed until the

fall of 1785, giving its adversaries an opportunity to mobilize

public opposition to it.

Arguments used in Virginia were similar to those that had been

employed in Massachusetts a few years earlier. Proponents of a

general religious tax, principally Anglicans, urged that it should

be supported on "Principles of Public Utility" because Christianity

offered the "best means of promoting Virtue, Peace, and Prosperity."

Opponents were led by Baptists, supported by Presbyterians (some of

whom vacillated on the issue), and theological liberals. As in

Massachusetts, they argued that government support of religion

corrupted it. Virginians also made a strong libertarian case that

government involvement in religion violated a people's civil and

natural rights.

James Madison, the leading opponent of government-supported

religion, combined both arguments in his celebrated Memorial and

Remonstrance. In the fall of 1785, Madison marshaled sufficient

legislative support to administer a decisive defeat to the effort to

levy religious taxes. In place of Henry's bill, Madison and his

allies passed in January 1786 Thomas Jefferson's famous Act for

Establishing Religious Freedom, which brought the debate in Virginia

to a close by severing, once and for all, the links between

government and religion. |

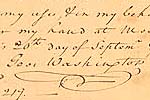

George Washington in

Support of Tax-Supported Religion George Washington in

Support of Tax-Supported Religion

In this letter George

Washington informs his friend and neighbor, George Mason, in the

midst of the public agitation over Patrick Henry's general

assessment bill, that he does not, in principle, oppose "making

people pay towards the support of that which they profess," although

he considers it "impolitic" to pass a measure that will disturb

public tranquility.

George

Washington to George Mason, October 3, 1785

Manuscript

copy, Letterbook 1785-1786

Manuscript Division, Library

of Congress (137)

![Richard Henry Lee to James Madison, November 26, 1784 [page one]](images/vc6649th.jpg) Another Supporter of

Tax-Supported Religion Another Supporter of

Tax-Supported Religion

Richard Henry Lee, who moved in

the Continental Congress, June 7, 1776, that the United States

declare its independence from Britain, supported Patrick Henry's

bill because he believed that the influence of religion was the

surest means of creating the virtuous citizens needed to make a

republican government work. His remark that "refiners may weave as

fine a web of reason as they please, but the experience of all times

shows religion to be the guardian of morals" appears to be aimed at

Thomas Jefferson who, at this point in his career, was thought by

other Virginians to believe that sufficient republican morality

could be instilled in the citizenry by instructing it solely in

history and the classics.

Richard

Henry Lee to James Madison, November 26, 1784

[page one] - [page

two] - [page

three] - [page

four]

Manuscript letter

Manuscript Division, Library

of Congress (143)

![Petition to the Virginia General Assembly, from Surry County, Virginia, November 14, 1785 [page one]](images/vc6692th.jpg) An Appeal for

Tax-Supported Religion An Appeal for

Tax-Supported Religion

The debate in Virginia in 1785

over religious taxation produced an unprecedented outpouring of

petitions to the General Assembly. This petition from supporters of

Patrick Henry's bill in Surry County declares that "the Christian

Religion is conducive to the happiness of Societies." They assert

that "True Religion is most friendly to social and political

Happiness--That a conscientious Regard to the approbation of

Almighty God lays the most effectual restraint on the vicious

passions of Mankind affords the most powerful incentive to the

faithful discharge of every social Duty and is consequently the most

solid Basis of private and public Virtue is a truth which has in

some measure been acknowledged at every Period of Time and in every

Corner of the Globe."

Petition

to the Virginia General Assembly, from Surry County, Virginia,

November 14, 1785

[page one] - [page

two] - [page

three] - [page

four] - [page

five]

Manuscript

The Library of Virginia

(138) |

PERSECUTION IN VIRGINIA

| In Virginia, religious persecution,

directed at Baptists and, to a lesser degree, at Presbyterians,

continued after the Declaration of Independence. The perpetrators

were members of the Church of England, sometimes acting as

vigilantes but often operating in tandem with local authorities.

Physical violence was usually reserved for Baptists, against whom

there was social as well as theological animosity. A notorious

instance of abuse in 1771 of a well-known Baptist preacher, "Swearin

Jack" Waller, was described by the victim: "The Parson of the Parish

[accompanied by the local sheriff] would keep running the end of his

horsewhip in [Waller's] mouth, laying his whip across the hymn book,

etc. When done singing [Waller] proceeded to prayer. In it he was

violently jerked off the stage; they caught him by the back part of

his neck, beat his head against the ground, sometimes up and

sometimes down, they carried him through the gate . . . where a

gentleman [the sheriff] gave him . . . twenty lashes with his

horsewhip."

The persecution of Baptists made a strong, negative impression on

many patriot leaders, whose loyalty to principles of civil liberty

exceeded their loyalty to the Church of England in which they were

raised. James Madison was not the only patriot to despair, as he did

in 1774, that the "diabolical Hell conceived principle of

persecution rages" in his native colony. Accordingly, civil

libertarians like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson joined Baptists

and Presbyterians to defeat the campaign for state financial

involvement in religion in Virginia.

|

![Summons to Nathaniel Saunders, August 22, 1772 [cover]](images/vc6697th.jpg) Unlawful

Preaching Unlawful

Preaching

Many Baptist ministers refused on principle to

apply to local authorities for a license to preach, as Virginia law

required, for they considered it intolerable to ask another man's

permission to preach the Gospel. As a result, they exposed

themselves to arrest for "unlawfull Preaching," as Nathaniel

Saunders (1735-1808) allegedly had done. Saunders, at this time, was

the minister of the Mountain Run Baptist Church in Orange County,

Virginia.

![Summons to Nathaniel Saunders, August 22, 1772 [summons]](images/vc6698th.jpg)

Summons to

Nathaniel Saunders, August 22, 1772 [cover] - [summons]

Manuscript

Virginia

Baptist Historical Society (140)

Dunking of Baptist Ministers

David Barrow was

pastor of the Mill Swamp Baptist Church in the Portsmouth, Virginia,

area. He and a "ministering brother," Edward Mintz, were conducting

a service in 1778, when they were attacked. "As soon as the hymn was

given out, a gang of well-dressed men came up to the stage . . . and

sang one of their obscene songs. Then they took to plunge both of

the preachers. They plunged Mr. Barrow twice, pressing him into the

mud, holding him down, nearly succeeding in drowning him . . . His

companion was plunged but once . . . Before these persecuted men

could change their clothes they were dragged from the house, and

driven off by these enraged churchmen."

The Dunking

of David Barrow and Edward Mintz in the Nansemond River,

1778

Oil on canvas by Sidney King, 1990

Virginia

Baptist Historical Society (141) |

Petition Against

Religious Taxation Petition Against

Religious Taxation

This anti-religious tax petition

(below), composed, scholars have assumed, by a Baptist and clearly

stating the Baptist point of view, was printed in large numbers and

circulated throughout central and southern Virginia. It was signed

by more citizens than any other document opposing Patrick Henry's

bill, including James Madison's more famous Memorial and

Remonstrance. What distinguished this petition from others was its

strong evangelical flavor. It argued that deism, which many of the

temporary allies of the Baptists espoused, could be "put to open

shame" by the exertions of preachers who were "inwardly moved by the

Holy Ghost." It also presented the Baptist reading of history,

namely, that the state ruined, rather than helped, religion by

supporting it.

Petition

to the Virginia General Assembly, Westmoreland County,

Virginia,

November 27, 1785 [left page] - [right

page]

The Library of Virginia (139)

Madison's Memorial and

Remonstrance Madison's Memorial and

Remonstrance

Madison's principal written contribution to

the contest over Henry's general assessment bill was his Memorial

and Remonstrance. Madison's petition has grown in stature over time

and is now regarded as one of the most significant American

statements on the issue of the relationship of government to

religion. Madison grounded his objection to Henry's bill on the

civil libertarian argument that it violated the citizen's

"unalienable" natural right to freedom of religion and on the

practical argument that government's embrace of religion had

inevitably harmed it. Thus, he combined and integrated the two

principal arguments used by opponents of Henry's bill.

To the

Honorable the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia:

A

Memorial and Remonstrance

Holograph manuscript, June

1785

James Madison

Manuscript Division, Library

of Congress (142)

Jefferson's Act for

Establishing Religious Freedom Jefferson's Act for

Establishing Religious Freedom

This act, the title of

which Jefferson directed to be inscribed on his tombstone as

comparable in importance to the Declaration of Independence, does

not exist in a handwritten copy. The version shown here was printed

as a broadside in London in 1786 by the great civil libertarian and

friend of America, Dr. Richard Price, who wrote the introduction and

made changes in the text. Jefferson evidently wrote the Bill for

Establishing Religious Freedom in 1777 as a part of his project to

revise the laws of his state. The Bill was debated in the General

Assembly in 1779 and was postponed after passing a second reading.

Madison revived it as an alternative to Henry's general assessment

bill and guided it to passage in the Virginia Assembly in January

1786.

An Act for

Establishing Religious Freedom, January 1786.

Thomas

Jefferson, Laidler, July 1786.

Broadside

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division,

Library of Congress

(144) |

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

SECTIONS: I. America as

Refuge - II. 18th Century

America

III. American

Revolution - IV. Congress of the

Confederation - V. State Governments

VI. Federal

Government - VII. New

Republic

Go to:

Library of Congress Library of Congress

Comments: Contact Us

(06/16/98) |

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

![A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts [right page]](images/f0503bth.jpg)

![A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts [left page]](images/f0503ath.jpg)

![Richard Henry Lee to James Madison, November 26, 1784 [page one]](images/vc6649th.jpg)

![Petition to the Virginia General Assembly, from Surry County, Virginia, November 14, 1785 [page one]](images/vc6692th.jpg)

![Summons to Nathaniel Saunders, August 22, 1772 [cover]](images/vc6697th.jpg)

![Summons to Nathaniel Saunders, August 22, 1772 [summons]](images/vc6698th.jpg)