HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

SECTIONS: I. America as

Refuge - II. 18th Century

America

III. American

Revolution - IV. Congress of the

Confederation - V. State

Governments

VI. Federal

Government - VII. New Republic

VII. Religion and the New Republic

The religion of the

new American republic was evangelicalism, which, between 1800 and the

Civil War, was the "grand absorbing theme" of American religious life.

During some years in the first half of the nineteenth century, revivals

(through which evangelicalism found expression) occurred so often that

religious publications that specialized in tracking them lost count. In

1827, for example, one journal exulted that "revivals, we rejoice to say,

are becoming too numerous in our country to admit of being generally

mentioned in our Record." During the years between the inaugurations of

Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln, historians see "evangelicalism

emerging as a kind of national church or national religion." The leaders

and ordinary members of the "evangelical empire" of the nineteenth century

were American patriots who subscribed to the views of the Founders that

religion was a "necessary spring" for republican government; they

believed, as a preacher in 1826 asserted, that there was "an association

between Religion and Patriotism." Converting their fellow citizens to

Christianity was, for them, an act that simultaneously saved souls and

saved the republic. The American Home Missionary Society assured its

supporters in 1826 that "we are doing the work of patriotism no less than

Christianity." With the disappearance of efforts by government to create

morality in the body politic (symbolized by the termination in 1833 of

Massachusetts's tax support for churches) evangelical, benevolent

societies assumed that role, bringing about what today might be called the

privatization of the responsibility for forming a virtuous citizenry.

The Atheist's

Bible The Atheist's

Bible

Pious Americans were shocked by Thomas Paine's

The Age of Reason, part of which was written during the great

pamphleteer's imprisonment in Paris during the French Revolution.

Although denounced as the "atheist's bible," Paine's work was

actually an exposition of a radical kind of deism and made an

attempt at critical biblical scholarship that anticipated modern

efforts. Paine created a scandal by his sardonic and irreverent

tone. Assertions that the virgin birth was "blasphemously obscene"

and other similarly provocative observations convinced many readers

that the treatise was the entering wedge in the United States of

French revolutionary "infidelity."

The Age

of Reason. Being an Investigation of True and Fabulous

Theology.

Thomas Paine. Philadelphia: Printed and sold

by the Booksellers, 1794

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division, Library of Congress (181)

Paine

Rebuked Paine

Rebuked

Even before the publication of the Age of

Reason, Thomas Paine was hated and feared for his political and

religious radicalism by conservatives in England, where he had

periodically lived since 1787. Paine fled to France in December 1792

to avoid trial for treason. In this cartoon, Paine sleeps on a straw

pillow wrapped in an American flag, inscribed "Vive L' America." In

his pocket is a copy of Common Sense. On the headboard are

his two "Guardian Angels": Charles James Fox and Joseph Priestley.

An imp drops a French Revolutionary song as he flees through a

window, draped in curtains decorated with the fleur-de-lis.

Confronting Paine are the spirits of three judges who will try him.

The presiding judge declares that Paine will die like a dog on the

gallows.

Tom

Paine's Nightly Pest.

Engraving by James Gillray.

London: published by H. Humphrey, 1792

Prints and Photographs

Division, Library of Congress (182)

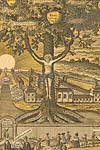

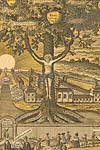

The Tree of

Life The Tree of

Life

The evangelical spirit was embodied in men like

John Hagerty (b. 1747), a Methodist preacher who established himself

as a Baltimore printer-publisher specializing in evangelical works.

Hagerty in 1791 published prints depicting a Tree of Life, a

Tree of Virtues and a Tree of Vices, motifs used in

religious art for centuries. The Tree of Life brings forth, under

the redemptive rays of God as Father, Spirit and Word, twelve fruits

of salvation for those seeking entry into the New Jerusalem. A large

crowd strolls by the narrow gate of salvation along the Broad Way to

the Devil and "babylon Mother of Harlots" beckon. The secure sinners

are stigmatized with labels indicating: "pride," "chambering &

wantonness," "quack," "usury," and "extortion."

The Tree

of Life

Hand-colored engraving. Baltimore: printed for

John Hagerty, 1791

Maryland Historical Society Library,

Baltimore, Maryland (183)

|

THE CAMP MEETING

| In 1800 major revivals that eventually

reached into almost every corner of the land began at opposite ends

of the country: the decorous Second Great Awakening in New England

and the exuberant Great Revival in Kentucky. The principal religious

innovation produced by the Kentucky revivals was the camp meeting.

The revivals were organized by Presbyterian ministers, who modeled

them after the extended outdoor "communion seasons," used by the

Presbyterian Church in Scotland, which frequently produced

emotional, demonstrative displays of religious conviction. In

Kentucky the pioneers loaded their families and provisions into

their wagons and drove to the Presbyterian meetings, where they

pitched tents and settled in for several days. When assembled in a

field or at the edge of a forest for a prolonged religious meeting,

the participants transformed the site into a camp meeting. The

religious revivals that swept the Kentucky camp meetings were so

intense and created such gusts of emotion that their original

sponsors, the Presbyterians, as well the Baptists, soon repudiated

them. The Methodists, however, adopted and eventually domesticated

camp meetings and introduced them into the eastern United States,

where for decades they were one of the evangelical signatures of the

denomination. |

Outdoor

Communion Outdoor

Communion

The Kentucky revivals originated with

Presbyterians and emerged from marathon outdoor "communion seasons,"

which were a feature of Presbyterian practice in Scotland.

Sacramental

Scene in a Western Forest

Lithograph by P.S. Duval,

ca. 1801, from Joseph

Smith, Old Redstone. Copyprint.

Philadelphia: 1854.

General Collections, Library of Congress

(184)

Camp Meeting

Plan Camp Meeting

Plan

This sketch, by Benjamin Latrobe, shows the layout

of an 1809 Methodist camp meeting in Fairfax County, Virginia. Note

that the men's seats were separated from the women's and the "negro

tents" from the whites.' This is an example of the racial

segregation that prompted black Methodists to withdraw from the

denomination a few years later and form their own independent

Methodist church. To accommodate the powerful, at times

uncontrollable, emotions generated at a camp meeting, Latrobe

indicated that, at the right of the main camp, the organizers had

erected "a boarded enclosure filled with straw, into which the

converted were thrown that they might kick about without injuring

themselves."

Plan of

the Camp, August 8, 1809

Journal of Benjamin

Latrobe,

August 23, 1806- August 8, 1809

Sketch by Benjamin

Henry Latrobe

Latrobe Papers, Manuscript Department, Maryland

Historical Society, Baltimore

(185) |

Religious Revival in

America Religious Revival in

America

In 1839 J. Maze Burbank exhibited at the Royal

Society in London this watercolor of "a camp meeting, or religious

revival in America, from a sketch taken on the spot." It is not

known where, when, or under whose auspices the revival painted by

Burbank occurred.

Religious

Camp Meeting.

Watercolor by J. Maze Burbank, c.

1839

Old Dartmouth Historical Society-New Bedford Whaling

Museum,

New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Gift of William F.

Havemeyer (187)

Methodist

camp meeting, March 1, 1819

Engraving

Prints and Photographs

Division, Library of Congress. (186)

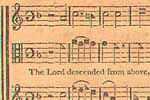

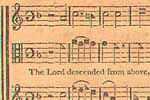

Revival

Hymnals Revival

Hymnals

Both of these books contain hymns that would

have been sung at nineteenth century revivals.

Samuel

Wakefield, The Christian's Harp . . . suited to the various

Metres

now in use among the different Religious Denominations . .

. in the United States

Pittsburgh: Johnston and

Stockton, 1837

The Easy

Instructor; or, A New Method of Teaching Sacred

Harmony.

William Little and William Smith.

Albany:

Websters & Skinner and Daniel Steele, c. 1798

Music Division, Library

of Congress (188-189) |

THE EMERGENCE OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN CHURCH

Bishops of the African

Methodist Episcopal Church Bishops of the African

Methodist Episcopal Church

In the center is Richard

Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, surrounded

by ten bishops of the church. At the upper left and right corners

are pictures of Wilberforce University and Payne Institute; other

scenes in the life of the church are depicted, including the sending

of missionaries to Haiti in 1824.

Bishops of

the A.M.E. Church.

Engraving by John H. W.

Burley,

Washington, D. C., 1876.

Boston: J. H. Daniels,

1876

Prints and

Photographs Division,

Library of Congress (190)

Woman Preacher of the

A.M.E. Church Woman Preacher of the

A.M.E. Church

The black churches were graced by eloquent

female preachers from their earliest days, although there was, as in

the white churches, resistance in many quarters to the idea of women

preaching the Gospel.

Mrs.

Juliann Jane Tillman,

Preacher of the A.M.E.

Church.

Engraving by P. S. Duval,

after a painting

by Alfred Hoffy, Philadelphia, 1844

Prints and Photographs

Division,

Library of Congress (191) |

Scholars disagree about the extent of the

native African content of black Christianity as it emerged in

eighteenth-century America, but there is no dispute that the

Christianity of the black population was grounded in evangelicalism.

The Second Great Awakening has been called the "central and defining

event in the development of Afro-Christianity." During these

revivals Baptists and Methodists converted large numbers of blacks.

However, many were disappointed at the treatment they received from

their fellow believers and at the backsliding in the commitment to

abolish slavery that many white Baptists and Methodists had

advocated immediately after the American Revolution. When their

discontent could not be contained, forceful black leaders followed

what was becoming an American habit--forming new denominations. In

1787 Richard Allen (1760-1831) and his colleagues in Philadelphia

broke away from the Methodist Church and in 1815 founded the African

Methodist Episcopal (A. M. E.) Church, which, along with independent

black Baptist congregations, flourished as the century progressed.

By 1846, the A. M. E. Church, which began with 8 clergy and 5

churches, had grown to 176 clergy, 296 churches, and 17,375 members.

|

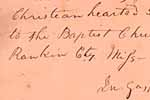

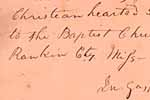

Christian

Charity Christian

Charity

In the letter below, a Mississippi Baptist

church informs a Virginia Baptist church that it has been approached

by a slave, Charity, who has been sold from Virginia to Mississippi,

but nevertheless wishes to let her old fellow church members in

Virginia know that she is praying for them and especially for "all

her old Mistress family." Charity also wants it known that "her most

pious affections and prayers" are that her old mistress, Mary S.

Garret (Garnett), "become prepared to meet her in heaven."

Mt.

Pisgah Baptist Church, Rankin City, Mississippi,

to Upper King

and Queen Baptist Church, Newtown, Virginia [left page] - [right

page]

Manuscript letter, June 1837.

Virginia

Baptist Historical Society (192)

Absalom

Jones Absalom

Jones

Born a slave in Delaware, Absalom Jones

(1746-1818), was a founding member of the African Episcopal Church

of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, dedicated on July 17, 1794. A year

later Jones was ordained as the first black Episcopal priest in the

United States.

Absalom

Jones

Oil on canvas on board by Raphaelle Peale,

1810

Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington. Gift of the Absalom Jones

School (193)

Congressional

Assistance to Absalom Jones

In this receipt, Absalom

Jones acknowledges receiving from Samuel Wetherill, a leader of the

Free Quakers of Philadelphia, a donation of $186, collected from

members of the House and Senate, to assist in promoting the mission

of Jones's "St. Thomases African Church in Philadelphia."

Receipt, signed by Absalom Jones, December 26,

1801

Manuscript

Division, Library of Congress (193a)

Religious

Exuberance Religious

Exuberance

Emotional exuberance was characteristic of

evangelical religion in both the white and black communities in the

first half of the nineteenth century.

Negro

Methodists Holding a Meeting in a Philadelphia

Alley.

Watercolor by John Lewis Krimmel

The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1942 (194)

Jerking

Exercise Jerking

Exercise

Lorenzo Dow (1777-1834) was a spellbinding but

eccentric traveling Methodist evangelist who could still a turbulent

camp meeting with "the sound of his voice or at the sight of his

fragile but awe-inspiring presence." Dow's audiences often exhibited

unusual physical manifestations under the influence of his

impassioned preaching.

Lorenzo

Dow and the Jerking Exercise.

Engraving by

Lossing-Barrett, from

Samuel G. Goodrich, Recollections of a

Lifetime.

Copyprint. New York: 1856

General Collections,

Library of Congress (195)

The

Shakers The

Shakers

The Shakers, or the United Society of Believers

in Christ's Second Coming, were founded by "Mother Ann Lee, a

stalwart in the "Shaking Quakers" who migrated to America from

England in 1774. American Shakers shared with the Quakers a devotion

to simplicity in conduct and demeanor and to spiritual equality.

They "acquired their nickname from their practice of whirling,

trembling or shaking during religious services." The Shakers used

dancing as a worship practice. They often danced in concentric

circles and sometimes in the style shown here. Shaker emissaries

from New York visited Kentucky in the early years of the nineteenth

century to assess the revivals under way there and made a modest

number of converts.

Shakers

near Lebanon state of N York, their mode of

worship.

Stipple and line engraving, drawn from

life.

Prints and

Photographs Division, Library of Congress (196)

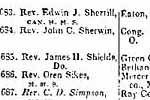

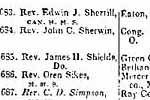

Nineteenth Century

Religious Leaders Nineteenth Century

Religious Leaders

Two of these pioneers, Barton Stone

and Alexander Campbell, were Presbyterian ministers who, for

different reasons, left the denomination and formed, in 1832, the

Disciples of Christ. While an active Presbyterian minister, Stone

organized the powerful Cane Ridge revival, near Lexington, Kentucky

in the summer of 1801.

Pioneers

in the Great Religious Reformation of the Nineteenth Century.

Steel engraving by J. C. Buttre,

after a drawing

by J. D. C. McFarland, c. 1885

Prints and Photographs

Division, Library of Congress

(197) |

THE MORMONS

| Another distinctive religious group, the

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or the Mormons, arose in

the 1820s during the "Golden Day of Democratic Evangelicalism." The

founder, Joseph Smith (1805-1844), and many of his earliest

followers grew up in an area of western New York called the "Burned

Over District," because it had been "scorched" by so many revivals.

Smith had been "seared but not consumed" by the exuberant

evangelicalism of the era. However the Mormon Church cannot be

considered as the product of revivalism or as a splintering off from

an existing Protestant denomination. It was sui generis, inspired by

what Smith described as revelations on a series of gold plates,

which he translated and published as the Book of Mormon in

1830. The new church conceived itself to be a restoration of

primitive Christianity, which other existing churches were

considered to have deserted. The Mormons subscribed to many orthodox

Christian beliefs but professed distinctive doctrines based on

post-biblical revelation. Persecuted from its inception, the Mormon

Church moved from New York to Ohio to Missouri to Illinois, where it

put down strong roots at Nauvoo. In 1844 the Nauvoo settlement was

devastated by its neighbors, and Smith and his brother were

murdered. This attack prompted the Mormons, under the leadership of

Brigham Young, to migrate to Utah, where the first parties arrived

in July 1847. The church today is a flourishing, worldwide

denomination. |

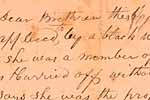

The Book of

Mormon The Book of

Mormon

The Book of Mormon, the fundamental

testament of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was

published by Joseph Smith in 1830. According to a standard reference

work, Smith translated it from "golden plates engraved in a language

referred to as reformed Egyptian.' The plates, which were seen and

handled by 11 witnesses, deal chiefly with the inhabitants of the

American continents spanning the period 600 B.C. to A.D. 421. The

plates relate the sacred history of Israelites who, led by a

divinely directed righteous man named Lehi, emigrated from Jerusalem

to the New World, where Christ appeared and gave them his teachings.

The record of their experiences, kept by various prophets, was

compiled and abridged by the 5th century prophet Mormon. . . ."

Book of

Mormon:

An Account written by the Hand of Mormon,

upon plates

taken from the Plates of Nephi

Joseph Smith, Junior.

Palmyra, N.Y.: E.B. Grandin, 1830

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division,

Library of Congress (198)

The Murder of Joseph and

Hiram Smith The Murder of Joseph and

Hiram Smith

The murder of Joseph Smith and his brother,

Hiram, by a mob in Carthage, Illinois, prompted the Mormons, under

the leadership of Brigham Young, to migrate in 1846-1847 to Utah,

where they found a permanent home. Although accounts differ, Joseph

Smith was apparently shot to death by a mob, one of whose members

approached him with the intention, which was thwarted, of beheading

him.

Martyrdom

of Joseph and Hiram Smith

in Carthage Jail, June 27,

1844

Tinted lithograph by Nagel &

Weingaertner,

after C. G. Crehen. New York: 1851

Prints and Photographs

Division,

Library of Congress

(199) |

BENEVOLENT SOCIETIES

The Distribution of

Religious Literature The Distribution of

Religious Literature

The American Tract Society, founded

in 1825, was one of the most influential of the scores of benevolent

societies that flourished in the United States in the first decades

of the nineteenth century. The Tract Society, through the efforts of

thousands of families like the one shown here, flooded the nation

with evangelical pamphlets, aimed at converting their recipients and

eradicating social vices like alcoholism and gambling that impeded

conversion. In the first decade of its existence the American Tract

Society is estimated to have distributed 35 million evangelical

books and tracts.

Family

handing out tracts

Woodcut by Anderson from

he

American Tract Magazine, August 1825.

American Tract Society,

Garland, Texas (205)

Mission to

Sailors Mission to

Sailors

Missionary societies in nineteenth-century

America left no stone unturned or no place unattended to convert

their fellow Americans. This church was built by the Young Men's

Church Missionary Society of New York to minister to visiting

seamen. A floating church, built to a similar design, was moored on

the Philadelphia waterfront.

The

Floating Church of Our Saviour...For Seamen (Built New York

Feb.15th, 1844. . . )

Steel engraving.

Copyprint

Prints and

Photographs Division, Library of Congress

(206) |

Benevolent societies were a new and

conspicuous feature of the American landscape during the first half

of the nineteenth century. Originally devoted to the salvation of

souls, although eventually to the eradication of every kind of

social ill, benevolent societies were the direct result of the

extraordinary energies generated by the evangelical

movement--specifically, by the "activism" resulting from conversion.

"The evidence of God's grace," the Presbyterian evangelist, Charles

G. Finney insisted, "was a person's benevolence toward others." The

evangelical establishment used this powerful network of voluntary,

ecumenical benevolent societies to Christianize the nation. The

earliest and most important of these organizations focused their

efforts on the conversion of sinners to the new birth or to the

creation of conditions (such as sobriety sought by temperance

societies) in which conversions could occur. The six largest

societies in 1826-1827 were all directly concerned with conversion:

the American Education Society, the American Board of Foreign

Missions, the American Bible Society, the American Sunday-School

Union, the American Tract Society, and the American Home Missionary

Society. |

![Evangelical tracts, American Tract Society. [Everlasting punishment]](images/vc6433th.jpg) ![Evangelical tracts, American Tract Society. [Are you saved.]](images/vc6432th.jpg)

Evangelical

tracts,

American Tract Society

[top

left] -- [top

right]

![Evangelical tracts, American Tract Society. [To the parents of Sabbath school children]](images/vc6435th.jpg) ![Evangelical tracts, American Tract Society. [Misery of the lost]](images/vc6434th.jpg)

[bottom

left] -- [bottom

right]

YA Pamphlet Collection

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division, Library of Congress. (201-4)

Missions to the Old

Northwest Missions to the Old

Northwest

The evangelical community was extremely

anxious about the supposedly deleterious moral impact of westward

expansion. Consequently, strenuous efforts were made to send

ministers to serve the mobile western populations. In this issue of

the Home Missionary, the journal of the American Home

Missionary Society, a map of the surveyed parts of Wisconsin was

published with a letter from a "correspondent at Green Bay," who

asserted, like the man from Macedonia, "that an immediate supply [of

ministers] is demanded." The executive Committee of the Society

decided "to make immediate and energetic efforts to supply Wisconsin

with the preaching of the Gospel.

The

surveyed part of Wisconsin.

Map from The Home

Missionary, volume XII, November 1839

New York: N. Currier,

c. 1839

General

Collections, Library of Congress (208)

Missionaries'

Reports Missionaries'

Reports

This table, compiled from data from the

missionaries of the American Home Mission Society, reports on

revivals in progress and other missionary activities under their

auspices in 1841-1842.

Missionary

Table from The Seventeenth Report of the American Home Missionary

Society

New York: William Osborn, 1842

American

Home Missionary Society Papers, Amistad Research Center,

Tulane

University, New Orleans (207)

Circuit

Preaching Circuit

Preaching

The Methodist Circuit rider, ministering to

the most remote, inhospitable parts of the nation, was one of the

most familiar symbols of the "evangelical empire" in the United

States. The saddle bags, seen here, belonged to the Reverend Samuel

E. Alford, who rode circuits in northwestern Virginia, eastern West

Virginia, and western Maryland.

The

Circuit Preacher

Engraving of a drawing by A. R.

Waud,

from Harper's Weekly, October 12, 1867.

Copyprint

Prints and

Photographs Division, Library of Congress (209)

Saddle

bags

Leather, used c. 1872-1889

Lovely Lane Museum

of United Methodist Historical Society, Baltimore (210)

Religion Indispensable

to Republican Government Religion Indispensable

to Republican Government

Tocqueville's impression of

American attitudes toward the relation of government and religion

was formed on his tour of the United States in the early 1830s

during the high tide of evangelicalism:

I do not know whether all Americans have a sincere

faith in their religion; for who can read the human heart? but I

am certain that they hold it to be indispensable to the

maintenance of republican institutions. This opinion is not

peculiar to a class of citizens or to a party, but it belongs to

the whole nation and to every rank of society.

Democracy

in America

Alexis de Tocqueville, Translated by Henry

Reeve

London: Saunders and Otley, 1835

Rare Book and Special

Collections Division, Library of Congress (211)

A Thousand Years of

Happiness A Thousand Years of

Happiness

Time lines that traced sacred history from

Adam and Eve to contemporary times were a popular form of religious

art in earlier periods of American history. The one seen here,

prepared by the well-known engraver, Amos Doolittle, states that in

1800 Americans entered a "fourth period" in which Satan would be

bound for "1000 years" and the church would be in a "happy

state."

The Epitome

of Ecclesiastical History

Engraving by Amos Doolittle.

New Haven: 1806

Enlarged

version

Rare Book

and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (212)

Due to the size of this object, it has been divided into four

sections, each one being in excess of 150 kilobytes

[upper left

quadrant] - [upper

right quadrant]

[lower left

quadrant] - [lower

right quadrant]

|

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

SECTIONS: I. America as

Refuge - II. 18th Century

America

III. American

Revolution - IV. Congress of the

Confederation - V. State

Governments

VI. Federal

Government - VII. New Republic

Go to:

Library of Congress Library of Congress

Comments: Contact Us

(10/17/2000) |

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

HOME

- EXHIBITION

OVERVIEW - OBJECT

LIST

![Route of the Mormon Pioneers from Nauvoo to Great Salt Lake, Feb'y 1846-July 1847. [right]](images/vc6590th.jpg)

![Route of the Mormon Pioneers from Nauvoo to Great Salt Lake, Feb'y 1846-July 1847. [left]](images/vc6589th.jpg)

![Evangelical tracts, American Tract Society. [Everlasting punishment]](images/vc6433th.jpg)

![Evangelical tracts, American Tract Society. [Are you saved.]](images/vc6432th.jpg)

![Evangelical tracts, American Tract Society. [To the parents of Sabbath school children]](images/vc6435th.jpg)

![Evangelical tracts, American Tract Society. [Misery of the lost]](images/vc6434th.jpg)